I met my brother at The Gate Picturehouse in West London the other night. We’d booked tickets to see the new Robert Eggers horror movie Nosferatu. The story is a reimagining of the Nosferatu mythos, which is based on Bram Stoker's original Dracula novel. The first Nosferatu adaptation of Dracula was released in the 1920s by a German production company, which hoped to avoid purchasing the copyright by slightly altering the story. These alterations amounted to little more than name changes. Count Dracula, for instance, became Count Orlok. Ultimately, Stoker's widow, Florence Stoker, sued the production company, and the legal costs led to its financial ruin. Despite a court order mandating the destruction of every copy, some prints of Nosferatu survived. Over time, the film gained recognition as a groundbreaking work in cinema and a cornerstone of the horror genre.

I’d been anticipating the film for a while. Last year I stayed in Bucharest, Romania, for a month, during which time I rented a car and drove across Transylvania to what has been dubbed ‘Dracula’s Castle’. Bran Castle is described on the website as Bram Stoker’s inspiration for the castle in his novel. However, I recently discovered that this claim is untrue. The Irish writer never visited Romania, and his description in the book doesn’t match Bran Castle. The only connection between Stoker’s tale and the castle seems to be his reading about the terrors committed by Vlad Drăculea, also known as Vlad the Impaler, a hero in present-day Romania. Vlad Drăculea gave the titular vampire his name and lived in Transylvania, but there’s no evidence he ever resided at Bran Castle. The claim linking the castle to Stoker’s villain appears to be tourism-driven. The castle’s website reads:

Bram Stoker never visited Romania. He depicted the imaginary Dracula’s castle based upon a description of Bran Castle that was available to him in turn-of-the-century Britain. Indeed, the imaginary depiction of Dracula’s Castle from the etching in the first edition of “Dracula” is strikingly similar to Bran Castle and no other in all of Romania.

Interesting. Some myth-making taking place here, but to line the coffers of someone other than the evil Count. That said, I had been anticipating Nosferatu because, as I said to my brother, I was looking forward to being back in that landscape. The barren white Transylvanian mountain ranges were indeed an inspiration for Stoker’s novel.

We left the cinema late that evening and walked through the coldest London streets I’d experienced for some time. We discussed the film. I won’t go into too many plot details in case you wish to see it. It is definitely worth the watch, more so than some other recent horror films – Heretic with Hugh Grant and Longlegs with Nicolas Cage, for instance, neither of which I particularly needed to have seen.

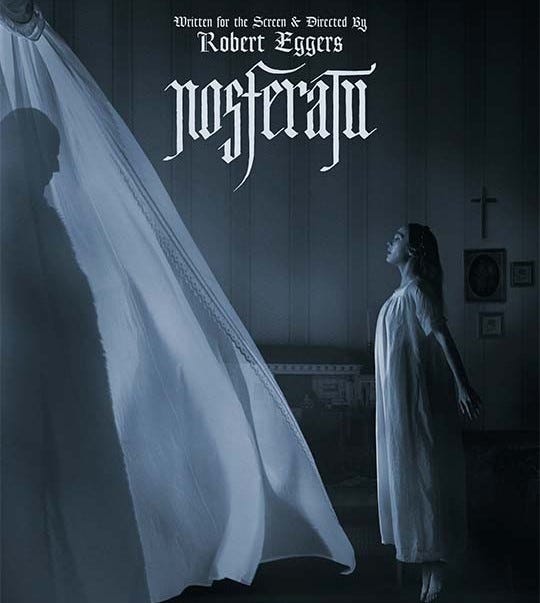

Horror is perhaps the most challenging genre. It relies so much more on image, on atmosphere – the slowly opening door, the tracking shot down an empty hallway, the stretching shadow of an emaciated hand across a wall. Image must be leveraged to a far greater extent than in other genres, which can rely more on the writing. To contrast with something like The Social Network, an Aaron Sorkin script, the heavy lifting is done primarily by the wonderful writing. That’s not to undermine David Fincher’s cinematography in The Social Network, which is exceptional.

But horror is another animal entirely. It’s difficult to make a truly great horror film. As my brother and I walked down Portobello Road, we agreed that for every one great horror film, there are perhaps a few hundred great films from more mainstream genres. This being said, far fewer horrors are made, so it’s an unfair comparison, but you get my point. Horror is possibly the most challenging genre.

The story of Nosferatu is compelling. As movie critic Mark Kermode put it, it’s a real romp. I enjoyed how the film explores the intersection between the spiritually demonic and the material realms. When Count Orlok journeys to mainland Germany, he brings with him both spiritual, symbolic trauma, as well as material destruction in the form of plague. This serves as a brilliant plot device, placing certain characters firmly within their respective realms. While Ellen Hutter, played by Lily-Rose Depp, occupies the spiritual realm, totally open and vulnerable to demonic forces, Aaron Taylor-Johnson’s character, Friedrich Harding, remains grounded in the material tragedies unfolding. This dynamic is useful as it allows us to track another main character, Thomas Hutter, played by Nicholas Hoult, as he transitions from material concerns to a greater spiritual awareness.

We continued to walk through the cold towards Maida Vale. The streets were empty. The biting frost that clung to the pavements had begun to freeze the garbage bags. If you bent down to pick one up, the black plastic would crumble in your hands. My brother mentioned how sometimes, while walking home like this, he’d look up at the highest penthouse apartments and imagine himself there during an apocalypse. I said I did the same, and ideally in one of the gated apartment complexes. The conversation must have been unconsciously driven by the plague in Nosferatu.

I love this mate - a very nice piece